Dr. Steve Hrop, a psychologist, achieved a peak US Chess rating of 2192 in 1988. His book Defending Under Pressure: Managing Your Emotions at the Chessboard was published in 2021 by Mongoose Press. This article is a review of Hrop’s book.

Candidate Moves

According to Dr. Steve Hrop, when our opponent plays a scary-looking move, our fight-or-flight response is triggered. We might play the first move that comes to mind, which could be disastrous. The two main ways to manage our heightened emotions are deep breathing and to find at least three candidate moves.

Looking for candidate moves is valuable advice! However, Hrop’s chess examples are confusing. Three of his 101 training positions (“T” followed by a number) are given below, to show some of the problems I had with Hrop’s book.

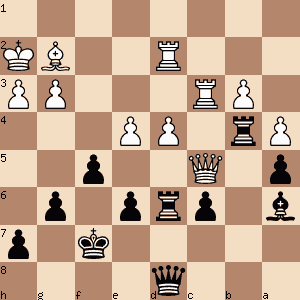

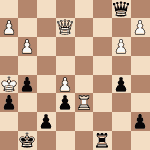

T4. Brandon Jacobson (2350) versus Steve Hrop (2100)

Jacobson is now a grandmaster, but he was 2350 at the time of this game. Hrop writes “I was rated over 2100 at the time.” Hrop does not give the year when this game was played.

Black to move.

Under the diagrammed position, Hrop gives four candidate moves for Black.

A…Rdxd4

B…Bc8

C…fxe4

D…Bb7

One of those choices, the move he played against Jacobson, is a bad move.

1…Rdxd4? Hrop writes, “After the exchange of a pair of rooks on d4, White played the simple Qa7+, winning my bishop.” From that sentence, I assume that Hrop took back on d4 with a rook. But recapturing with the rook makes what is a bad move (1…Rdxd4) even worse. 2.Rxd4 Rxd4? That is, why not take with the queen on d4? Then Black is still much worse but does not lose a bishop. Hrop never discusses this option. 2…Qxd4 3.Qxc6 (3.Qa7+?? is terrible now because it loses White’s queen. 3…Qxa7) 3…Rb6 4.Qc7+ Kf8. 3.Qa7+ and Black ended up losing, 1–0.

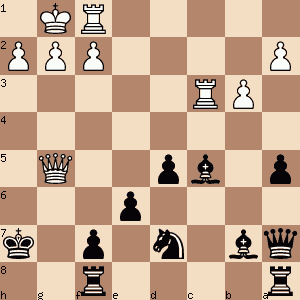

T10. Laurent Fressinet versus Robert Kempinski

Bundesliga, 2009

Black to move

Hrop writes, “Begin by identifying all candidate moves that prevent White from checkmating on the next move with Rc3–h3. There are three candidates. Did you find all three?” I found 1…Be3, or 1…Nf6 with the idea next move of 2…Nh5. A third candidate move, 1…Bxf2+, also delays checkmate. However, Hrop never tells what the three candidate moves are! So, I don’t know if my three candidates are the correct ones. He only discusses 1…Be3.

1…Be3! Hrop numbers 1…Be3 as move 1. Also, his book has figurine algebraic notation for text and annotations. So instead of a “B” as I have written, imagine the image of a bishop in figurine notation. 1…Nf6 2.Rh3+ Nh5 3.Rxh5#; 1…Bxf2+ 2.Rxf2 Qxf2+ 3.Kxf2 Nf6 4.Rh3+ Nh5 5.Rxh5# 2.Rxe3 Qxe3 3.fxe3 f6 The actual Fressinet-Kempinski game was drawn 10 moves later, on move 37. 27…f6 was the move numbering in the game, ½–½.

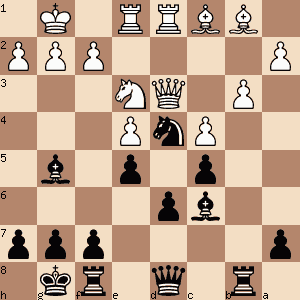

T25. Yevgeny Feldman (2300) versus Steve Hrop (2100)

Marshall Chess Club, 2013

Black to move.

Hrop writes, “Black has a solid defensive position and is fully developed. Nevertheless, that does not mean he should become overly cautious in an attempt to achieve a draw against a higher-rated player.” Hrop recommends the move that he played, 1…a5.

1…a5 the Stockfish 14.1 engine evaluates this position as more than a pawn advantage for Black. 1…g6 Stockfish 14.1 also evaluates the position after 1…g6 as more than a pawn advantage for Black. Hrop eventually drew against Feldman, ½–½.

Why go for a draw?

The T25 position, from Feldman versus Hrop, raises an important emotional struggle: Does one play for a win or for a draw against a higher-rated opponent? Hrop seems to indicate that he is playing for a draw against Feldman in T25, despite having an advantage. Is playing for a draw the best strategy for one’s emotions, to keep our hopes modest? Or does aiming for draws inhibit our improvement? Answers to these questions, about our goals and fears around playing higher-rated opponents, are not addressed. Likewise, emotions about facing lower-rated opponents are not discussed. Yet emotions can be triggered when we see our opponent’s rating differs from our own. A discussion of expectations and emotions would have been helpful.

While I can’t recommend Defending Under Pressure: Managing Your Emotions at the Chessboard, it did teach me to identify at least three candidate moves in each position. As Hrop writes, considering candidate moves turns each position into a multiple-choice question, which is easier to answer than an open-ended question.

It’s hard to understand why the reviewer had issues with the three positions she chose from my book to critique. Regarding position T10, she states that “Hrop never tells what the three candidate moves are! So, I don’t know if my three candidates are the correct ones. He only discusses 1…Be3.” I only discussed …Be3 because it is the only WINNING move. All other candidate moves are totally losing for Black! So it makes no sense to complain that I did not list the other “correct” candidate moves! An author doesn’t have enough space to discuss every candidate move. Readers have to do a lot of that work on their own. In position T25, she states that “Hrop seems to indicate that he is playing for a draw against Feldman”. I’m not sure how she drew that conclusion. I was making a broader point that many players often play it too safe and go for the draw in such positions. As I said numerous times in the book, when players adopt that mindset, they often slowly get outplayed by the higher-rated player. By playing the active move …a5, I realized I had a small advantage and was eager to avoid falling into the “play it safe” trap. She also states that “our goals and fears around playing higher-rated opponents are not addressed”. The reason for not addressing that issue is that the focus of the book (as reflected in the title) is managing your emotions at the chessboard when handling a specific position on the board. The book was not intended to provide advice about your feelings in general regarding players much stronger or weaker than you (e.g., when you see on the wall chart that you’ve just been paired against someone much higher-rated). Finally, the reviewer states that “his book has figurine algebraic notation”, as if that’s unique to my book or is something negative. In fact, almost all chess books these days are published in figurine algebraic. She then instructs her readers to mentally translate her use of letters (e.g., “B” = bishop) into figurine images. I fail to see the point in that tangential advice.