International Master and famed chess trainer Mark Dvoretsky called serious endgame errors by strong players “tragicomedies.” In Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual, he advised his readers to not laugh at the players, but to see the perils of ignoring endgame theory.

Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual (5th edition) was published in 2020 by Russell Enterprises, Inc. An excerpt, reviews, details, and pricing are available at this link. Dvoretsky died in 2016. The fifth edition was revised by Grandmaster Karsten Müller, with help from Grandmaster Alex Fishbein.

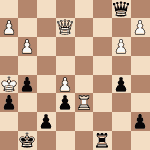

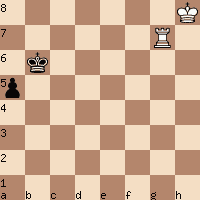

The following position is the second of “25 Tough Positions” in a different book, Gambit Publications’ Desert Island Chess Puzzle Omnibus by Grandmasters Wesley So, Michael Adams, John Nunn, and FIDE Master Graham Burgess. After I answered the “tough position” incorrectly, I reviewed the appropriate section in Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual (5th edition) to understand my error.

Click to reveal the solution

White must separate Black’s king from its pawn with 53. Rc4+!

Grandmaster John Nunn gives the reader three choices: 53. Rg1+, 53. Kd6, or 53. Rc4+.

Turning the position into his own “tragicomedy,” International Master Elliott Winslow played 53. Rg1+? FIDE Master Kyron Griffith, who has two International Master norms, pounced on Winslow’s mistake. Griffith drew the game rather than losing. Griffith won the New In Chess Swindle Award 2020 for a different game, where he turned a loss into a win.

Like Winslow, I also picked a wrong move. But I chose a different wrong move, 53. Kd6? I thought that the obvious idea is for White’s king to shepherd its pawn to its c8-promotion square. I felt my rook was already on the perfect file, supporting the c-pawn as it promotes. However, my choice allows Black’s king to escort its pawn to its f1-promotion square. What’s needed is to prevent Black from executing his plan before diving into White’s plan.

In a previous SparkChess column, I mentioned that FIDE Master Paul Whitehead knew how to use a rook to separate an enemy king from its pawn. Clearly, I didn’t learn Whitehead’s lesson, which is needed here.

Grandmaster John Nunn gives winning lines after that move, as this “tough puzzle” is in his 100-puzzle section of the Desert Island Chess Puzzle Omnibus. Likewise, Winslow analyzed the win he missed in the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Room Newsletter #902. Winslow added that he had “about a minute” left on his chess clock when he played 53. Rg1+?

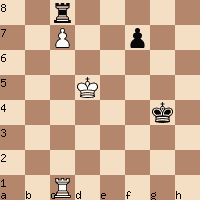

The analyses by Nunn and by Winslow work because they hinder Black’s king support of its pawn’s progress. Dvoretsky calls this “Cutting the King Off.” Can you find the right move for White in Dvoretsky’s position below?

Click to reveal the solution

Rg5

Dvoretsky wrote, “When the black pawn reaches a3 it will be eliminated by

means of Rg3 (the pawn may even come to a2 and then perish after Rg1 followed

by Ra1).”

I get these positions wrong because I aim to place my rook behind my opponent’s passed pawn or in front of that pawn. In other words, I try to put my rook on the same file as the enemy’s passed pawn. Here, for example, I might choose Rg1 with the idea of Ra1, getting in front of the pawn. Or I might play Rg8 with the idea of Ra8, getting behind the pawn. Those ideas allow Black’s king and pawn to march together toward White’s first rank, drawing. I am slowly learning that, in some positions, a rook should be placed on a rank that separates the enemy pawn from the enemy king.