Over the next several Mastering Chess articles you’re going to gain a much better understanding of each piece, and how to make the most of them. We’re going to start out with the knight, because it’s the only piece that doesn’t move in a straight line.

This makes the powers of the knight mysterious to many players.

So now we’re going to unveil that mystery. That means by the time you’re done reading this article series, you will travel a long way towards making the most of your knights.

Success Guidelines

- Knights need outposts. That’s a square that can’t be attacked by a pawn. A knight can often dominate a position when it occupies a strong square and can’t be removed.

- Knights increase in strength as they move down the board. That’s because they can’t travel a long distance, but they can move in all directions. A knight posted on the fifth or sixth rank is often (but not always!) the best minor piece on the board

- Knights are usually better than bishops in closed positions. That’s because they can jump over pawn chains that block other pieces.

- A knight is usually the best piece to blockade a passed pawn. That’s because the knight does not lose any mobility on the blockading square. It can still jump forward at any time.

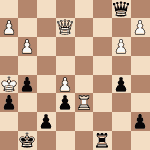

The biggest key to getting full value from your knight is finding a good outpost

The biggest key to getting full value from your knight is finding a good outpost. Some squares are much better than others, so let’s look at the key qualities of an ideal square. The more of these qualities you discover … the better the square !

What Makes a Good Outpost for Your Knight

- It exerts influence over a key sector (center, kingside, or queenside). Assess which sector is the most important, and look for an outpost in that area of the board.

- It pressures a key weakness from its post.

- It makes it difficult for the opponent to maneuver his pieces. This especially holds true for the queen and rook. That’s because they’re “higher value pieces” and the opponent usually can’t afford to let the knight capture them. This means they have to maneuver around squares controlled by the knight.

- It threatens to win material or checkmate the king.

- The outpost is well supported by pawns, pieces, or both. The classic example of a great outpost is a square on a half-open file, protected by a pawn and a rook.

In our next two articles we’ll show you examples that illustrate the qualities of a good outpost. First, we’ll focus on how to create and preserve an outpost for your knights. In the final article, you’ll clearly see the nature of an “unsustainable outpost,” and what can happen to a knight when it can’t find a place to call home.

Make Sure the Knight’s Outpost is Sustainable

In the sample game contained in the second article, both of my opponent’s knights are temporarily well-posted and active. However, neither one is able to secure the square on a long-term basis, and must ultimately retreat.

Speaking broadly, it’s perfectly okay when the knight has to retreat if either (a) it has served a useful purpose in the meantime, or (b) its temporary influence from its post can be converted into a new advantage.

It’s important to remember there is an opportunity cost connected with any knight sequence. That cost is represented by the time it takes to maneuver its way to the post.